This interview with Jim Stonecipher, who is Managing Director of EdyMac LLC, was conducted by the editor of Jet Fuel Intelligence (JFI), Cristina Haus. It originally appeared in the JFI issue of Nov. 7, 2025, and is republished here with the kind permission of Energy Intelligence Group, the publisher of JFI.

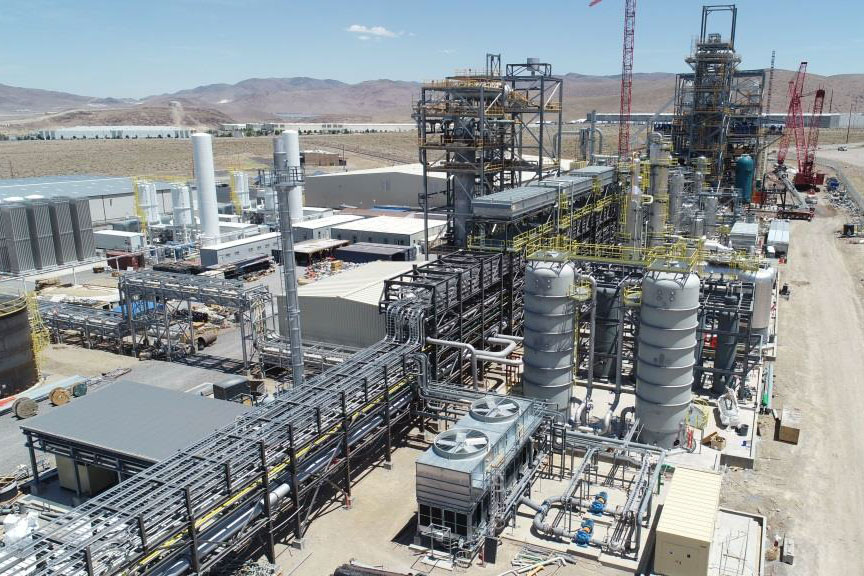

Like a once-thriving frontier town, the remnants of the Fulcrum BioEnergy plant in the desert near Reno, Nevada, illustrate the challenges of designing, building and operating a novel plant to produce sustainable aviation fuel from municipal solid waste. Fulcrum laid off most of its staff in May 2024 and filed for Chapter 11 that September. The building site was listed for auction and sold in late 2024, while other assets were sold or settled through the bankruptcy court. Jim Stonecipher learned from his involvement helping to bring that plant from ‘steel in the ground’ to first production how to avoid the pitfalls that bedevil first-of-a-kind (FOAK) projects. As Managing Director of EdyMac, he now provides advice on strategy, management, project development and operational consultation. In an interview with Energy Intelligence, he describes the lessons learned from his three decades of experience in that sphere.

Q: Fulcrum had lined up investors, had a proven Fischer-Tropsch technology and offtake agreements with airlines. What were some of the key issues that caused it to fail?

A: Several case studies could be written on Fulcrum, so I will focus on some of the key areas. In the first place, the process was not fully tested end-to-end in the pilot plant. Fulcrum added a substantial process step to the plant design after the pilot plant testing was concluded. This step was highly disruptive during initial start-up and resulted in significant damage to key equipment, causing several months’ delay to repair the equipment during a time that month-to-month spending was at its peak.

Another issue was Fulcrum’s choice of engineering and construction company, Abengoa, which had underbid the job and wasn’t up to the task of designing and building a plant of this complexity. Aside from its low bid, Abengoa was chosen for its willingness to provide a performance wrap to support the financing Fulcrum needed. Abengoa went bankrupt during construction and its contract was terminated during the Covid-19 pandemic. Fulcrum then undertook the job of completing the work by hiring other construction companies. Pandemic-related days made it much more expensive than originally thought and severely drained Fulcrum’s balance sheet.

Q: What key lessons were learned from that experience?

A: For me, the key lessons were that new chemical processes must be tested end-to-end, even if this is just a new use for a tried operation. Issues will be discovered during the pilot phase; they may be small or they may be huge, but solving them on a small platform is much faster and cheaper in the pilot plant than in a commercial-scale unit.

You also need to define what success looks like for the investors the company is attracting. Don’t aspire to achieve an outcome, and when faced with disappointment look to change the metric to something less and expect the investors to embrace it. Some of my key measures are product yield and plant reliability/uptime. If the plant has an expected yield and runs consistently, the cost and effort to deal with a capacity shortfall is much easier to define.

When building a FOAK plant, make sure there is flexibility in what is deployed. Because the operating envelope is not known, it can’t be over-optimised or lack operating margins, and you can’t create additional land easily if needed. Once the FOAK is running, the design can be improved and optimised. And don’t expect the FOAK to make money initially. The return on investment (ROI) comes from the many of a kind, not the FOAK.

Q: How do you view the current investment climate for SAF projects?

A: The climate for SAF projects is tough right now. The issues at Fulcrum and the artificial intelligence market have drawn attention away from the infrastructure projects like SAF. US policy uncertainty and a short timeline to safe harbour in 2027 for US projects is dampening investor interest unless they are a strategic player, where having access to the product is the driver for them.

Q: Why do you think major oil firms like BP and Shell are pulling out of announced projects?

A: BP and Shell are pulling back because of economics – pure and simple. Both of their projects used waste oil feedstock and the hydro-processed esters and fatty acids (HEFA) process to make SAF. BP indicated they don’t see the expected growth in SAF usage to justify the project, even with SAF blending rates expected to jump in 2030 when the UK and EU SAF mandate levels increase. This may also be an indication that Shell and SAF modelled an expected rise in feedstock cost that would pinch the margins, or that they expect UK/EU regulators to soften the mandate levels. While green projects are not favoured by the investment communities due to the currently low rate of return, HEFA is a highly developed and low-risk technology.

So if the economics do not pan out to the point of taking significant write-downs, that means the ROI wasn’t there. Since the EU is an expensive market to do business in, the capital expenditure may have made the project ROI too low as well. Also pertinent to its decision is the fact that BP is strategically shifting its CAPEX monies into more traditional oil and gas projects, and the optics of where it is spending its money could have also played a role. As UK/EU mandates come into greater play by the end of the decade, they will have more effect on the overall value of SAF and project economics.

Q: How do you keep investors from pulling out at every stage of the process?

A: A vision of milestones has to be given early in the investment relationship and adhered to. Unfortunately, quite often early-stage companies overstate expected results to attract investment with the hope they can fix any issues before they come to light and the initial equity will keep the investor anchored if there are delays. But investors are learning that companies overstate and under-deliver, so their economic model builds in a slower ROI and reduces their appetite for projects. This flawed approach has to change for both parties. It creates a false relationship and does not build trust.

Q: What role do the US Renewable Fuels Standard (RFS) and state incentives play in the commercial viability of SAF projects?

A: RFS does add some lift via its Renewable Identification Number (RIN) values, but economic viability cannot be based on RINs, Low Carbon Fuel Standards (LCFS) or federal tax credits. These may support an earlier payback on the CAPEX, but the operational expenditure needs to stand on its own versus fossil alternatives, which is the main challenge at this point. The facility size does not have the economies of scale, so the fixed cost burden is high in comparison to much larger fossil-based producers with mostly depreciated assets. State incentives are also not a decider, but they do influence the overall value of the final product and the economics due to logistics and credits.

Q: How do you reconcile the trade-off of producing SAF versus renewable diesel?

A: It’s a decision based on economics alone. In many cases, the ability to steer a plant towards diesel production over Jet A isn’t too dramatic a change for an operator. In either case, both products are adding to the overall energy security for the region and broadening the portfolio of possible pathways.

Q: What is the most important factor to reach the commercial stage?

A: There is no one factor as each pathway and project has many unique elements that influence viability. From a regulatory perspective, the rules have to be stable and not subject to political whim every four years. Lack of policy certainty in the US is killing investment, not the lack of incentives or mandates. For technology vendors, the process must be tested end-to-end. These vendors must come together and form working groups to demonstrate that each element of the process works together. They also need to engineer a complete process that can occur at an accelerated pace, which reduces the development capital needed to get to a final investment decision (FID). For developers, there is no shortcut to FID, first production or sustained operation. This comes through careful planning, working through the issues and early preparation. The developer also needs to be able to take an honest look at the project and stop, just like BP and Shell, if it does not meet the economic threshold, instead of chopping equipment, short-cutting steps and hoping for an improved environment.

Q: What are some of the engineering challenges?

A: With the exception of HEFA processes, no one has ever done any engineering for a FOAK plant. They may have similar project experience, but by its nature, the project has never been done. The developer’s selection of the engineering contractor is critical and the engineering partner has to be able to operate outside the normal bounds of a well-defined project scope. The developer needs to bring additional technical and operational expertise to the table with the engineer to make sure the knowledge is transferred into the design.

Q: What are the main challenges around feedstock?

A: Forecasts for the availability of fats, oils and greases, which feed the HEFA pathway to SAF, indicate that feedstock limits may emerge in the 2030s. From a process chemistry standpoint, HEFA and ethanol processes are well-demonstrated and low-risk opportunities, but have tightening feedstock availability in the forecast. Other feedstocks that are not directly in the food chain do overlap with arable land use. They also compete with ethanol needed to meet motor fuel blending for the RFS and LCFS.

Agricultural and wood products are the next generation of feedstock. They are highly uniform in handling and content – either a waste product of growing food or, in the case of wood, there is over-abundance due to much lower demand for pulp and paper. Agricultural waste has no aggregation system to bring in and store the large quantities needed. It is also highly seasonal, making it a challenge for use all 12 months. Wood can be harvested year-round, has an aggregation system in place in many communities and is highly available in some regions globally. The main issues with agricultural waste and wood are the conversion technology to take the energy of these feedstocks, since there is no large-scale demonstration reference in recent history beyond simple incineration or combustion for heat.

Use of municipal solid waste- or refuse-derived fuel is the most abundant, universally available feedstock around the world with a built-in aggregation process. But it lacks a demonstrated conversion technology that has a high carbon monoxide yield, is highly inconsistent in content and presents some unknown contaminants during processing. It is also difficult to handle due to high variability, a moist consistency and significant quantities of materials that the conversion process cannot break down.

Q: What do you mean by risk register, and how do you manage that?

A: A risk register is a list of unresolved items or issues that have been given a probability of occurring and have significance for the project, equipment, people or community should they occur. It’s built to help drive priority to items that have more impact, which in this case is a negative impact, and not lose track of the many items on the radar scheme of a project developer. If properly used, the risk register is never empty, but the amount of risk lessens over time.

Q: What are the challenges of going from a pilot plant to a commercial size facility?

A: Assuming the pilot plant runs the same process as the commercial scale, the primary challenge is operating larger size equipment that may not behave the same way the smaller equipment did. As the equipment grows in size, stresses that were not apparent in the pilot plant begin to show: equipment breaks, chemistry does not react as expected, materials don’t move as expected, contaminant levels are higher. Fixing these issues on a commercial scale takes more time and money. Remedies also need to be worked out when the company has its highest cost burden, hitting the balance sheet hard. Other issues come from using a different type of equipment in the pilot plant than in the commercial scale plant. While heating, cooling and pumping may not seem that different, the time to discover there is a problem is not when the spending is at its peak and the balance sheet at its lowest.

Photo (Fulcrum BioEnergy): The former Fulcrum Sierra facility

More News & Features

Early data shows uncertainty that UK SAF mandate can be met in its first year

SkyTeam announces airline finalists of its competition to drive action on sustainability

News Roundup December 2025

Swiss advanced SAF technology startups Metafuels and Synhelion reach project milestones

ICAO releases first-ever growth factor for airlines’ CORSIA offsetting requirements

PtX fuels have significant Asia-Pacific potential but face many barriers, finds report